How I Created a Language From Scratch and What I Learned in the Process

Includes an immersive voice over version

Latest update on Spirit-Girl #1: We are in the same holding pattern regarding the production of the comic. We have received shipment of some of the inks but several others are still pending arrival. In the meantime I’m working on the Spirit-Girl #2 script and layouts. I’m also doing some world building that will affect Spirit-Girl #3 and beyond. This article is about that world building project. It is for paid subscribers only but free subscribers will have access to it in 3 months.

If you do not already have a free subscription to this newsletter, please consider subscribing now. You can also take out a paid subscription to support me. You will get early access to some content and special perks to be announced in the future.

Oh-heuk’alba!

This is how you greet a friend in the language of the K’al people. It means: It is good for us to be together and of common ancestry. More on this at the end of the article.

First Steps

When I was a little boy I would sometimes zone out and pretend I was speaking another language. My Dad once overheard me doing this and, impressed, he remarked that he could even make out the different characters in the gibberish. A bit embarrassed, I stopped doing this sort of play.

I was often drawn into the zone like this as a child. Now I know this is a phenomenon called “immersion”. It’s one of my favourite things about comics; the high potential for immersion. Think about how few obstacles there are between the imagination of a person and a comic book page. Unlike movies or video games comics have no budget limitations. There is also no committee to appease (hopefully). Whatever you imagine can flow through the pencil and pour onto the page.

I remember reading Tintin. I would spend hours looking over each page, hearing the scrnch scrnch of footsteps in snow under the whistling wind, feeling the cold biting my cheeks.

Though I prefer comics to movies, video games or Tabletop Role-Playing Games (TTRPGs) whenever I do engage with those media, it is the immersion which interests me the most.

For video games it’s Skyrim I like. The expansive open experience, deeply fleshed out world, hidden locations and stories, a soulful and haunting soundtrack (which I’m listening to while writing this article) all make for an immersive experience. In Skyrim, you can talk to people and they will tell you a little story. You can read books about cosmology, history, politics or more low brow subject matter. When playing video games I quickly get bored of fight mechanics and I end up just grinding through quests so I can get to the next bits of story and lore.

When I played TTRPGs what was of interest to me was the promise of inhabiting a story. To the patient frustration of others at the table, I tended to be more interested in the lore books than the rule books. I also liked make puns with friends. I have good memories of that. But it turns out my calling was not to play stories but instead to create them.

Worldbuilding

The detail work that goes into making a world feel real and alive is called Worldbuilding. One of the masters of this art is J. R. R. Tolkien. As an example: In The Lord of the Rings the elves aren’t just humans with long ears. They have an entire culture that is revealed in pieces as the reader explores the narrative. The elves - and other races - even have a language all their own, with multiple dialects! Being a philologist, Tolkien made the languages up from scratch. Elvish has its own phonemes, vocabulary and grammar. Most readers will breeze by the elvish passages in the books or be thankful for subtitles in the movies. But the care and time put into making elvish sound distinct and believable is an important feature that enhances the immersion. When the inscription appears on the ring of power for the first time, it evokes the sense of a larger world. This opens up the imagination to possibility. I believe that putting in the work to try and achieve some of that in my comics is worth the effort. So I decided to try my hand at making a language.

About Conlangs

Made up languages are called conlangs (Con-structed Lang-uages). Conlangs are divided into three subtypes:

Artlangs: Artistic languages. Artlangs are conlangs that are designed for fictional purposes, for personal use or just for fun. The most popular artlang is Klingon, a language spoken by a warrior race in Star Trek. According to Mark Okrand, its creator, Klingon is spoken by up to 30 000 real world speakers earning it an entry in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Auxlangs: These are made up languages that are used in non-fictional situations where two sets of people need a bridge language. Esperanto is the most famous of these.

Engelangs: These languages are not meant for general use. They are engineered to test linguistic theories. Lojban is one of these. It’s meant to be based exclusively in logic and reason and tests the theory that languages place strictures on the thinking of those who speak it. Another experimental language is Ithkuil, an engelang designed to be maximally precise. Lojban has a handful of fans who speak the language but no one speaks Ithkuil.

Our area of interest is Artlanging. Here is what I learned in making one from scratch.

How I Made A Language From Scratch

Clarifying Goals

This is step #1. Before jumping in you have to know what you want out of the conlanging project. For me it’s to have my characters speak and write a fictional language that sounds believable as a secret ancestor of French. There is some discussion in the philology world about why French sounds different to other Latin languages. To me this is a crag where I can fit my fictional people and their stories. French is an important influence on the world of Northland (the name of my fictional world) so my conlang has to sound a little like French but must be different enough to sound like a distant cousin language to French.

It would be cool to construct my language so thoroughly as to make it possible and easy for readers to learn to speak it. But is too ambitious and beyond my level of skill and training. The goal is to make a language that is developed enough for me to be able to translate texts and for it to feel real when others read it. I could just throw around some gibberish but I don’t like the thought of anyone exploring a bit deeper and being disappointed that there’s no semblance of a real language. Explorers should be rewarded for exploring.

Another aim of mine with this language is to have it say something about the culture of the people who speak it. This is to add to the immersiveness of the stories.

And finally, my conlang should be relatively easy (with practice) for me to translate texts.

The goal is threefold:

Dinstinctiveness and believability.

Creation of story potential and reader immersion.

Ease of use.

Choosing Sounds

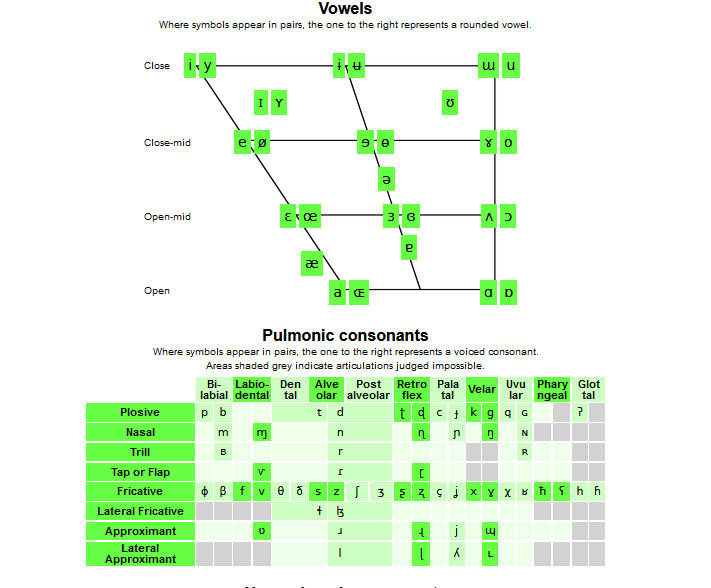

This is step #2. All languages start spoken and so to build a language you must choose a limited collection of sounds. These are called phonemes. I used an online guide to conlanging. There are thousands. All of them suggest the same first step. So I proceeded to choose my phonemes. Using the International Phonetic Alphabet chart, I picked a series of sounds that overlap with the French ones but reduced the amount. The complexity compounds as the project moves along so it’s best to keep it simple at the start. I also added one phoneme which is completely foreign to French. It’s called a “velar ejective stop”. It is written down as k’. Velars are consonants articulated with the back part of the tongue against the soft palate. This is not present in any Latin language so adding it to my conlang helps give it an “otherness” feel.

Making Up Words

Step #4: Now the task became to build up a short list of words using only the set of phonemes I selected. I used the Swadesh List as my base set of words. This list is a set of 100 - 207 words that are theorized to be common to all languages. But I swapped some out as I deemed fit. I don’t think I need a word for “louse”. But I do need a word for “mountain”.

Building up this vocabulary was an excellent exercise that spurred my imagination. I had to consider the history of how the K’al have lived over thousands of years. That history has an effect on how a people think and this will be reflected in their language.

If you ever embark on an conlanging project my top piece of advice would be to have the willingness to go back and make a lot of changes. You’ll soon be dealing with a lot of moving parts. If you are too attached to your early decisions you will pay for it when the level of complexity shoots straight up. Which brings us to our next step.

Making a grammar

Step #5: This was and still is the toughest part for me. Up to this point everything felt fairly easy and fun. But grammar starts introducing structure to the language which requires a lot of mental juggling. It can get tough to keep it all straight.

First you have to decide on a word order pattern. Linguist Mark Okrand says that language isn’t so much governed by rules than by patterns. For instance English tends to have a Subject Verb Object word order. The sentence Dog bites man has a completely different meaning than Man bites dog. Who is biting and who is bitten are indicated only by word order. Therefore, S.V.O. is the pattern of English but there are exceptions. French also has an S.V.O pattern.

I chose to change this up for my conlang to avoid creating what in conlanging circles is called a relex. A relex is a conlang that is too close a reflection of one’s own birth language. It’s a lot easier to handle a relex because you can just translate everything word for word. But two languages having the exact same grammatical structure is not something that exists in reality. So if you are not careful and you end up with a relex conlang, it will not be believable. You have to pull up your sleeves and put in the work to make a grammar that is distinct enough so as to not ruin immersion.

I chose the Verb Subject Object word order pattern. This pattern is not super rare and is found in some Celtic languages. It makes sense that a more or less European people might also have such a grammatical pattern to their language. But it’s different enough to Latin languages that it’s not a stretch that it would belong to a lost branch of European history.

But this is just the beginning. How about verbs? How about tenses? What kinds of prefixes and suffixes will exist? Possessives? As a non-linguist I found no easy way to tackle all of these challenges. I just had to try some things and experiment to see what happened. When I encountered challenges I worked to solve them. I jumped from problem to problem like this for a few weeks. I went back and forth making adjustments until I had a grammar I could wrap my mind around. I won’t go into the grammatical details here because I have doubts this is of interest to more than a very few people. Maybe someday I will formalize my notes and publish them. Suffice to say I have built a rudimentary grammar missing only certain trickier parts of language like future perfect continuous and stuff like that.

Translation

This is step #6: Now is the time to put your work to the test. Hopefully at this point you’ve done a bunch of smaller tests and made adjustments as you went along. It’s important to start early on to try and say basic things in your conlang just to get a feel for how it’s progressing. Doing so avoids having to do huge redesigns.

I want my fictional people to be able to say more than “I drink water” and “We climb mountains”. Translating larger and more complex texts helps helps feel out the outer boundaries of the conlang. When translating you will have to make up words from whole cloth or from root words in your Swadesh list. You will add these to your expanding dictionary. At this point you will see the many limitations of your conlang and have to fix some problems. I am currently still working on this step.

Simultaneously I’m working on building a dictionary. It’s absurd to make up a conlang word for every word in the dictionary. And it’s not necessary. But I am going through each letter of the dictionary and scanning quickly for basic words that I need to translate. It’s especially useful to think about what I call “particle” words. Words like: at, and, but, if, or. You don’t need to translate those. Instead you might decide to create some grammatical rules which will serve to express those ideas.

Writing system

This is step #7: Now that you’ve translated all this phonetically, you may need a writing system. Because what I’m working on is a comic book and comics is a visual medium, it is necessary that my conlang have a writing system. I remember studying Korean and being amazed by the simplicity of their phonetic writing system. Inspired by this I decided that I would use a similar approach. This serves a dual purpose: it makes it easy for me to use and expresses that the culture is pragmatic.

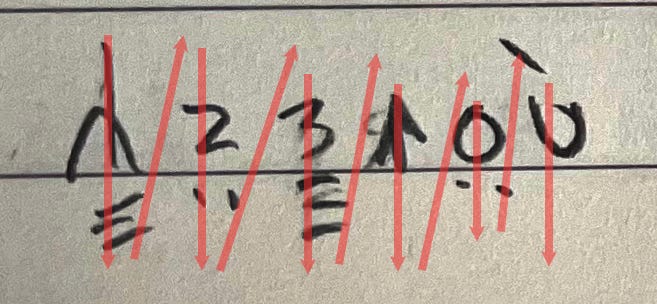

Each glyph in K’al is associated with a vowel or consonant sound. Each word is written out using consonants. Vowels are accents placed on the bottom or top of the consonants to indicate whether the vowel is spoken before or after the consonants. There is one glyph which is silent so that vowels can be written standalone. This also allows for multiple vowels to be placed in sequence or to repeat vowels to indicate a long sounded vowel. The writing reads left to write in an up and down zig zag pattern as shown in this image.

It is usually suggested to have a script variant of one’s writing system. I have not worked on this. I expect I will eventually. But for now I just want to nail down all the necessary elements of grammar, finish the dictionary and work on translating texts which will appear in the comics.

Demoing the K’al Conlang

I prefer not to reveal too much more about the culture of the people who speak K’al. I think it’s more immersive for the readers to discover things as they explore the stories. But I will provide a little piece of translation work I’ve done.

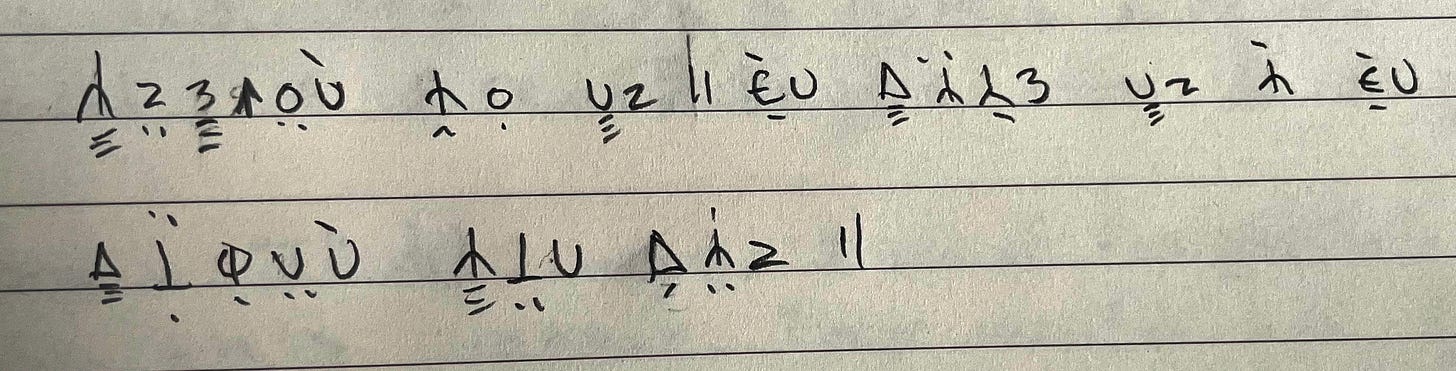

The sentence translated is: “I went for a nice walk in the forest. The trees were very tall and I could hear the birds chirping.”

This becomes: Tuhzamuhsbaèl toubi luhz. Èshèl vuhatrèm luhz èt èshèl vuhak’idèlaèl tuhk’al véitaz.

This means, roughly: Of walking in a good way I was among trees. Mountain-like were those trees and heard I birds.

Written down it looks like this.

You’ll notice one special characteristic of K’al when you see the literal translation say “Of walking” and “mountain-like”. The K’al language depends largely on analogy, comparison and metaphor. There is no word for tall. But there is a word for mountain. And so the trees are said to be mountain-like. There is room for interpretation and so it’s not a precise language. It’s a poetic language. Precision is achieved by shared experience and familiarity amongst the speakers. There is potential for individual stylistic flair. Maybe your cousin is a hunter and so his metaphors will need to be interpreted through that lens. An outsider may learn the technicalities of the K’al language but not be able to speak it. They would need to immerse themselves in the culture in order to communicate effectively.

Conclusion

Making up pretend languages isn’t just child’s play. Lots of adults not only make up languages but some of them even make a career of it. Turns out making up pretend languages is serious business. I guess my own childhood conlanging exploits were not something to be embarrassed about.

If you see ever see a child embarrassed at making up pretend words reassure them they have the support of 30 000 Klingons.

Until next time,

Qapla!

I'm impressed too. The dedication and love you are putting into behind the scenes work will pay off. Thanks for sharing!

Darn, that's brilliant (clapping of hands) I'm really impressed by all this!